pi beta phi settlement school

Emma Harper Turner was determined for Pi Beta Phi to find altruistic work large enough to hold the interest of the national organization. In May 1911, Gatlinburg was chosen as the site of a settlement school.

Emma Harper Turner was determined for Pi Beta Phi to find altruistic work large enough to hold the interest of the national organization. In May 1911, Gatlinburg was chosen as the site of a settlement school.

During the 1910 Swarthmore Convention, the Washington, D.C. Alumnae Club (represented by Emma Harper Turner) proposed that “the alumnae of the Fraternity be given power to found and maintain a school to be dedicated on the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Fraternity, in honor of the founders of Pi Beta Phi.” It was deemed the most significant act of convention, as  Grand President May Lansfield Keller said, “We have done a big thing in a short time.”

Grand President May Lansfield Keller said, “We have done a big thing in a short time.”

Emma Harper Turner was determined for Pi Beta Phi to find altruistic work large enough to hold the interest of the national organization. Individual chapters had sometimes adventured in altruism before, but never all of the chapters together. It was also very important alumnae were involved in the project.

Locating a site for the Settlement School was a daunting task because of the rural and mountainous terrain. A committee traveled to Knoxville and made excursions into the mountain districts designated by the U.S. Bureau of Education as those most in need of schools. Travel to Gatlinburg was over some of the worst roads in Tennessee. The schools were mainly one-room wooden structures. Few of the teachers had ever attended high school and were teaching at the same level they had completed (never above the fifth grade). Abject poverty was the norm and living conditions were rugged. The cabins were small and overcrowded; the sanitary facilities were primitive. The area was deprived of the benefits of higher education, household economics, health care and scientific farming. Several sites, including one at Wears Valley, were considered.

In May 1911, Gatlinburg was chosen as the school site because it was felt that Pi Phi could truly make a difference in the lives of its residents. An appropriation of $500 from the Fraternity’s Endowment Fund set the plan in motion.

To read about the first visit to Gatlinburg, written by May Lansfield Keller, see Appendix 1.

Martha Hill of Nashville, an experienced mountain teacher, was hired as the first teacher. The Pi Beta Phi Settlement School opened in March 1912 with 14 students. It closed three months later with 33 students. This first Pi Beta Phi Settlement School was held in the old school building at the junction of Baskins Creek and Little Pigeon River.

Many alumnae clubs were interested in the Settlement School project and by March 15, 1912, donations totaled $2,775.63. In addition to money, some clubs sent gifts. The Washington and Baltimore Alumnae Clubs sacrificed their Founders’ Day banquet and instead sent an organ to be used for musical programs. The Los Angeles Alumnae Club sent table silver and the Boston Alumnae Club gave linens. Other clubs sent a sewing machine, window shades, rugs, books, a cereal double-boiler, sheets, bird pictures, napkins, dishtowels and 12 yards of blackboard cloth.

Many alumnae clubs were interested in the Settlement School project and by March 15, 1912, donations totaled $2,775.63. In addition to money, some clubs sent gifts. The Washington and Baltimore Alumnae Clubs sacrificed their Founders’ Day banquet and instead sent an organ to be used for musical programs. The Los Angeles Alumnae Club sent table silver and the Boston Alumnae Club gave linens. Other clubs sent a sewing machine, window shades, rugs, books, a cereal double-boiler, sheets, bird pictures, napkins, dishtowels and 12 yards of blackboard cloth.

Elizabeth Clarke Helmick, Michigan Alpha, a member of the Washington, D.C. Alumnae Club became Chairman and Treasurer of the new committee when the project was proposed. The Settlement School Committee recommended that Miss Hill be kept on and that the Chicago Alumnae Club assume control of the project. Grand Council gave the Chicago Alumnae Club responsibility for the Settlement School.

In the summer of 1912, Mrs. Helmick made a trip to Gatlinburg with the purpose of selecting a building site. She called a community meeting and told the people about Pi Beta Phi and explained the Fraternity proposed to give the community a permanent, lasting gift of a new school. There were some fears from the community that the school was nothing more than a cover for an organized church. After Mrs. Helmick spoke, she asked for questions but there were none. Finally she called Mr. Ogle, the native teacher, by name. Scrambling to his feet, he asked in a determined and agitated voice, “What church do you folks belong to?” Mrs. Helmick replied, “No one church, and yet to all the Christian churches.” Her explanation placated the crowd. The women begged that the school remain. Two of the strongest supporters were Mr. and Mrs. Andy Huff. They were progressive people and wanted education for their four school-age children.

In trying to find a suitable building site, Mrs. Helmick told Mr. Huff that in the progressive West where she lived, when an enterprise like the Settlement School thought of coming to a place permanently, “It was customary that if the people wanted it, for the business men to get together and offer an inducement to its coming.” She explained that she had been obliged to hunt up properties and to urge men to put a reasonable valuation upon their land when they had a month before expressed a desire to sell. Mr. Huff took his cue and before Mrs. Helmick left that afternoon, he met her on the road to tell her, “We men have gotten together and if you folks want the Ogle place, and you feel $2,000 is too much, I have a man who will give you $800 for the store, and if $1,200 is more than you want to pay, we propose making up the difference among us. We want your school right here. We know Miss Hill, and we know what you have done. We will stand together and do anything you wish to keep you here.”

The next day County Superintendent J.S. Keeble made the proposition that Pi Beta Phi take entire charge of the school management in the Gatlinburg district. He offered to give a clear, absolute deed to all the public school property, including a new building valued at $1,000, which stood on a hill overlooking Gatlinburg. School authorities would also annually turn over, in cash, teachers' salaries, as long as Pi Beta Phi maintained a public and free school in the lower grades.

December 3, 1912 marked the start of a new school term. Della “Miss Dell” Morgan Gillette, Illinois Zeta, was the first Pi Beta Phi alumna to be hired at the school. On the first day, 40 students came, and by January 75 were enrolled. Some had to be refused because of space limitations, one of them being Mr. Ogle, the public school teacher. Miss Dell, on her first Christmas there, introduced the students and their families to a Christmas celebration.

As the school year progressed, girls from the surrounding area were organized by Miss Dell into a sewing club. While the girls worked on their sewing projects, Miss Dell read to them. Two boys’ baseball teams were formed. When school ended in late March, it was the first time the children had gone to school for eight months in one year.

Mrs. Helmick and Miss Miller turned their attention to acquiring land. Although several places were considered, the only desirable tract was owned by E.E. Ogle. The men of the village did not think he would sell even if the money could be raised. Mrs. Helmick spoke with Mr. Ogle and found he would sell for $1,800. If the Fraternity would put in $600 and the men of the community $1,200, the land no doubt could be obtained. Mrs. Helmick also issued an ultimatum saying that if the Ogle land was not obtained for the Fraternity by the next day at noon, Pi Beta Phi would go elsewhere and establish a school where land would be given to us.

“The Dream,” Kate Miller Remembers

We now wondered what they would do. They were at last convinced that ‘those wimmin’ meant what they said. We packed our trunks, began to get the household things ready to leave until we should have them sent elsewhere, ordered the hack from Sevierville to come for us the next day, and wondered what the next 24 hours would bring forth. Mr. Huff was sent for in his lumber camp eight miles away; everyone gave up his business and those who had no business gave that up, all more deeply excited than they had ever been. We were now to see the miracle, these mountain men and women, moved by their very strong desire to keep the fraternity school, forgot their reserve, threw off their easy going ways, and went to work for a community enterprise. Never before had they cooperated for a public affair. They said that there was no one who could go ahead, but the necessity for a leader developed one, and Andy Huff was drawn forth. As I think back over the stirring weeks, it seems to me that nothing which came out of them will be of greater good to these men and women than this: the knowledge that they can do things themselves. Tuesday evening we had many callers, three of the women staying until after dark. They said they just couldn’t let us go, that they knew the men would try their best, but that perhaps they couldn’t raise enough money. For women in the mountains to stay out after dark was a violation of their social code, but they were forgetting even their social customs now. The next morning while we were at breakfast, Mr. Huff and Steve Whaley came to get us to draw up a subscription paper. Mrs. Helmick wrote the heading for one, putting Pi Beta Phi down for $600. Andy Huff put down $250 and Steve Whaley $250 … After the men left, Mrs. Huff came to us and told us of her dream. … It seemed that she had dreamt that she and the children were all down by the riverbank playing. The children had pushed through the bushes and had slipped down to the riverbed where they were playing on the dry gravely bottom in the pools. She had stayed up on the road, and suddenly she looked up the river to the distant mountains that seemed to close it in. There she saw rising and clinging to the mountain sides a ‘big steam, a fog.’ Then the fog began to roll in clouds, and to come down the river slowly. It kept getting bigger and bigger and kept rolling and rolling down towards the place where the children were playing. Her eyes grew large and her voice tense as the vividness of her vision came back to her. She repeated again and again: ‘The fog kept rolling and rolling and getting bigger and bigger and coming down to get my children.’ Up the river she also saw, in the path of the oncoming danger, the Reagan and Ownby children. She thought that the fog was going to get them as well as her own children. She was frightened, she said that her ‘heart roared like a pheasant.’ She tried to go down to the children but she couldn’t go through the dense bushes. She knew that the fog would get her children. Just then she saw Andy going to them. The relief she must have felt in her dream at this moment was fully evidenced in her voice. She knew that ‘Andy would save them.’ Then when she wakened, and wakened Andy and told him her dream, she told him that he had just got to make ‘the women’ stay if it took every cent he had.

Mrs. Huff’s dream played a large part in working the miracle of raising the necessary money. Just before noon Mr. Ogle came up to say that he would give as much as anyone toward the price. He would give $250. He said that he would “rather have the school than his land — provided he could get a fair price for the land.” The hack had arrived to take the two Pi Phis to Sevierville. Soon after its arrival word was sent that the Pi Phis were wanted at the store. The whole town seemed to be crowded around; when the Pi Phis arrived, they found Mr. Ogle busily writing a title bond to be held by Pi Beta Phi until the deed could be made and sworn to. Almost all the money had been subscribed and Mr. Huff and Mr. Maples agreed to make up any final deficit. Young Charley Ogle collected all the firecrackers remaining from the 4th of July celebration and set them off so that everyone would know that Pi Phi would stay in Gatlinburg.

Mrs. Huff’s dream played a large part in working the miracle of raising the necessary money. Just before noon Mr. Ogle came up to say that he would give as much as anyone toward the price. He would give $250. He said that he would “rather have the school than his land — provided he could get a fair price for the land.” The hack had arrived to take the two Pi Phis to Sevierville. Soon after its arrival word was sent that the Pi Phis were wanted at the store. The whole town seemed to be crowded around; when the Pi Phis arrived, they found Mr. Ogle busily writing a title bond to be held by Pi Beta Phi until the deed could be made and sworn to. Almost all the money had been subscribed and Mr. Huff and Mr. Maples agreed to make up any final deficit. Young Charley Ogle collected all the firecrackers remaining from the 4th of July celebration and set them off so that everyone would know that Pi Phi would stay in Gatlinburg.

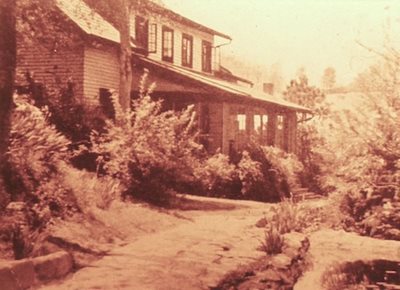

With the deed to the Ogle land, Pi Phi acquired 35 acres, a teacher’s cottage, an old but useful school building, a barn, a store, several storage buildings and according to Mrs. Helmick, “an immense amount of faith in the generous support and good will of Pi Phis everywhere.” In return, Pi Phi promised to maintain a school for 10 years, build a new schoolhouse and provide good teachers.

A new school building was designed by Mr. and Mrs. Von Holst of Chicago. Lucy Hammond Von Holst was a Colorado Beta and a member of the Chicago Alumnae Club. This new building, a one-story frame structure 60 by 84 feet, resembled a bungalow and cost $3,735.30. It was the second largest schoolhouse in the county.

That summer, Miss Hill resigned because of health issues. When school opened on August 4, 1913, it was Kate Miller, of the Settlement School Committee, who assisted Abbie Langmaid, Minnesota Alpha. That was the beginning of the first year in Pi Phi's own building and with teachers who were all Pi Phis. Two months later, Miss Langmaid was succeeded by Mary O. Pollard, Vermont Alpha, who was made head resident.

The new school building was dedicated on July 9, 1914. Five members of Grand Council — May Lansfield Keller, Lida Burkhard Lardner, Amy Burnham Onken, Anne Stuart and Sarah Rugg Pomeroy — attended and assisted in preparing for the guests whom they entertained at a luncheon.

Conditions for the teachers were crowded, and after the 1914–1915 school year it was recommended that a new teacher’s residence be constructed. During the autumn of 1916, a 10-room teacher’s residence was designed and planned by Alda and Almina Wilson, Iowa Gammas and experienced architects working in New York City. It was built as a model home; it had furnace heat, running water and a bath. It was modern in every respect. All materials except the lumber were freighted over the rough roads from the “outside.” The carpentry work was done entirely by mountain men under the guidance of an experienced builder. The building cost $4,748.43. With dedicated teachers, its own schoolhouse and the new teacher’s cottage, the Settlement School became a respected and integral part of the Gatlinburg community.

From the start, the teachers and head residents tried to educate the students and community members about health issues. Mary Pollard, first head resident, remembered years later spending the summer of 1914 walking the community telling residents about the danger of hookworm. Treatment could be sought at the Settlement School where the country hookworm specialist visited. In 1914, the Settlement School Committee reported that a fund had been started by three of the founders. They had contributed $150 for the establishment of a hospital in Gatlinburg to honor Jennie Nicol.

It has been said that the 1919 influenza epidemic broke down the walls of mistrust and prejudice that existed at the school’s beginning. Evelyn “Miss Evelyn” Bishop, New York Alpha, was hired as head resident in 1917. When the influenza epidemic broke out, the community turned to the school for help. Under Miss Bishop’s competent direction, not one case proved fatal.

Attempts were made during the 1919–1920 school year to enlist the services of a school nurse. In the summer of 1920, Miss Evelyn attended a meeting of the New York City Alumnae Club and told them of the lack of health care in Gatlinburg. She said there was no doctor, no nurse and no hospital in the immediate area. Her appeal was heard by Ontario Alpha Phyllis Higginbotham, who volunteered her services. Nurse Phyllis, as she was known, was a graduate of the University of Toronto, Johns Hopkins University and Columbia University. She had served overseas in World War I and at the time of her hire was doing settlement work in New York City. When Nurse Phyllis arrived in Gatlinburg, there was not another registered nurse in the county. In addition, she had no office, no supplies and nothing except a great need.

Attempts were made during the 1919–1920 school year to enlist the services of a school nurse. In the summer of 1920, Miss Evelyn attended a meeting of the New York City Alumnae Club and told them of the lack of health care in Gatlinburg. She said there was no doctor, no nurse and no hospital in the immediate area. Her appeal was heard by Ontario Alpha Phyllis Higginbotham, who volunteered her services. Nurse Phyllis, as she was known, was a graduate of the University of Toronto, Johns Hopkins University and Columbia University. She had served overseas in World War I and at the time of her hire was doing settlement work in New York City. When Nurse Phyllis arrived in Gatlinburg, there was not another registered nurse in the county. In addition, she had no office, no supplies and nothing except a great need.

Shortly after Nurse Phyllis arrived, the Pi Phis bought the farm of Andrew Ogle. The property included a four-room home, which was turned into a health center and emergency hospital. On May 8, 1922, this hospital was dedicated as the Jennie Nicol Memorial Health Center and Emergency Hospital. It included an office and consulting room, a work room, a bathroom and a linen closet where sterile supplies were kept. Visiting doctors could perform emergency operations in the hospital.

Nurse Phyllis’ professionalism as well as her personality won the cooperation of four doctors from Sevierville and Knoxville, and they each agreed to keep office hours once a month at the health center, as did a Knoxville dentist. Within six years, Nurse Phyllis had built up such a fine center that one of the leading doctors at the State Medical University at Memphis wrote a detailed report advising the state to use this rural health center as a model for other rural health facilities. In 1926, Nurse Phyllis resigned to become State Supervisor of Public Health Nurses, a position she was offered because of her many accomplishments in Gatlinburg.

In 1948, a new Jennie Nicol Memorial Health Center was dedicated. Located on the Parkway near the Arrowcraft Shop, it was made possible largely through bequests and special gifts. The Andrew Ogle home, which had been the health center, became the Settlement School caretaker’s residence. The new Jennie Nicol Health Center continued serving the needs of the community for almost 45 years until 1965 when it closed. By that time, there were many doctors in each town, and one-room schools had been replaced with modern school buildings. The building still stands, a testament to the service provided to the citizens by the Fraternity and its staff of dedicated nurses and teachers.

It was inevitable that the Settlement School would feel the impact of the rapid change when the Great Smoky Mountains National Park became a reality. As the government bought up land for the park, the mountain people moved down to the lower elevations, many moving to Gatlinburg. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park was dedicated in 1941 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Thousands of tourists and new residents were drawn to the area. The town population grew from 500 in 1928 to more than 2,000 in the mid-1960s.

Those who owned land in Gatlinburg heeded Andy Huff’s advice and held on to it. Many say the education they received at the Pi Beta Phi Settlement School helped them cope and capitalize upon this new prosperity. Motels, gift shops and restaurants starting springing up after the park’s dedication ceremonies in 1941.

As Gatlinburg grew, the responsibilities of the Pi Beta Phi Settlement School also grew to keep pace with the community’s needs. Home economics was emphasized as was vocational education. The men of the community were instructed in furniture making. A two-week lyceum course was held for the adults of the community. Music was taught, and entertainment provided. A Parent-Teachers’ Association was formed. A class for older students was established. These students did not know how to read or write, but they had been too embarrassed and ashamed to start school with the younger children.

The 1922 meeting of the Settlement School Committee and Grand Council empowered the Settlement School to establish a junior high school and industrial high school, to install a moving picture machine in the auditorium of the new building, to add a course in agriculture in accordance with the Smith-Hughes Act and to establish scholarships. They also named the original cottage the Mary Pollard Cottage in recognition of her “loyalty and worthy service to the Fraternity as the first Pi Beta Phi head resident.” Perhaps one of the greatest efforts to come out of this era was the development of the cottage craft industry, which became known as Arrowcraft.

In the mid-1920s, the county increased the regular free school term to eight months, and a telephone was installed at the school. In 1928, the Pi Beta Phi High School was built. It housed the Grace Coolidge Library, which was started in 1924; by 1930, some 3,500 volumes had been cataloged. When a new junior high school and an industrial high school were built, Pi Phi maintained dormitories in which the students could be boarded and supervised.

In the 1930s, vocational agriculture continued to be strong. A Future Farmers of America chapter was established. In 1933, Miss Evelyn resigned as director of the school. During her 15 years, “new departments were created and added to the school, the standard of work in all handicrafts was greatly raised, extension work was organized and became a wonderful success at Sugarlands and outlying districts, the mountain children were taught to play and develop as all splendid Americans should, scientific farming became established and the fine new Administration Building became a reality. The people who live up and down the creeks and hollers that lead into Gatlinburg now live happier, healthier and more prosperous lives because they were privileged to have Miss Evelyn.”

To read Dr. William S. Taylor's, Dean of the College of Education and the University of Kentucky, opinion of the work of Pi Beta Phi in Gatlinburg, see Appendix 2.

Crafts had always been a part of the mountain peoples’ lives, but because there was no market for the things they made, they either used the crafts themselves or they bartered them for goods that they needed. Basket making was given its first real consideration at the Settlement School when Margaret Burroughs, Texas Alpha, stopped at the school for a week in the fall of 1914 and gathered together a class of girls who were interested in basket weaving. It had been an old industry, but the baskets had been made for personal household use.

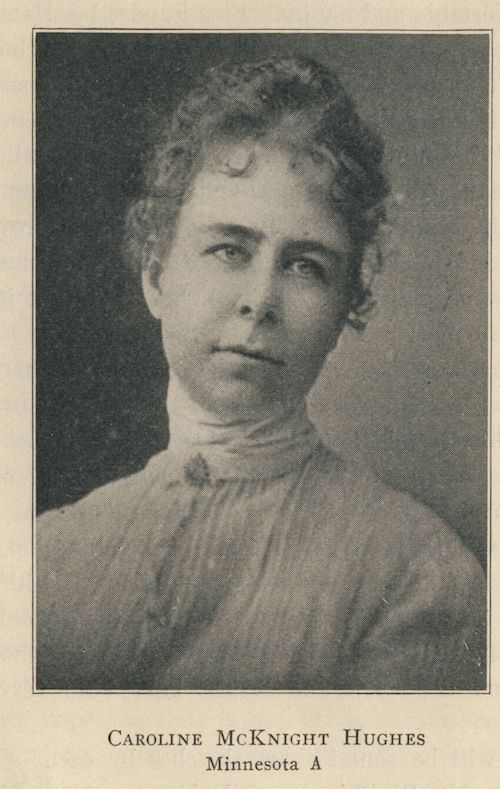

In May of 1915, Minnesota Alpha Caroline McKnight Hughes (pictured) took charge of the business and industrial work. She installed a manual training outfit at a cost of $179 with which she gave instruction to 52 boys

In May of 1915, Minnesota Alpha Caroline McKnight Hughes (pictured) took charge of the business and industrial work. She installed a manual training outfit at a cost of $179 with which she gave instruction to 52 boys

After the Pi Phis worked diligently to secure funding, the weaving department was equipped. Spinning bees and quilting parties were held in the hope of reviving these almost lost industries. Miss Hughes taught the children how to weave tiny rugs, mats and hammocks. Basket making continued as a fireside industry. By the spring of 1919, baskets, ranging in price from 40 cents for a small basket to $5 for a fireside basket, were for sale. They were made from hemlock bark, willow switches, willow bark, white oak splits and corn husks. It took patience and perseverance to raise the standard of workmanship among the basket makers. The best basket makers were starting to find a market among the visitors to the hotel. But all the basket makers felt they should get the same amount regardless of the quality. They did not understand the concept of consignment, so the school became the employer. Baskets were bought from the basket makers and then resold. In an attempt to encourage the less experienced workers, the school bought some baskets that were not up to standard. Yet, in 1919, it was reported that about 1,000 baskets had been sold.

In 1920, the weaving department benefited when Lucy Nicholson of Berea was hired to teach weaving. Interest was immediately revived among the women of Gatlinburg. Mrs. Anderson and Mary Ogle had their own looms and began making rugs and table scarves. The tourists at the hotel provided a small market for the goods. Three looms were added to the school’s equipment in 1921, and by the end of the year six looms were in use and six were lent out. The girls and women made goods to sell to the summer tourist trade.

Chairman of the Fireside Industries Committee, Nita Hill Stark, sent letters to alumnae clubs. Slides and a display were prepared for display at the 1924 Eastern Conference. In 1925, Winogene Reddings, a weaving teacher, was employed full time and she provided instruction to the women of the community. Originality and excellence in new design and color combinations were stressed. Orders began to increase. The total of weaving orders increased from $1,000 in 1923 to $14,000 in 1927. By 1936, 91 looms were furnishing products for the school.

To read more about the economic development in the area and the beginning of Arrowcraft, see Apendix 3.

Two surveys of the Settlement School programs were made in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Edwin Holton, a Dean at Kansas State University, conducted one of the surveys, and Dr. William Taylor, Dean of the University of Kentucky’s College of Education, supervised the other. Both studies recommended that the cost of maintaining Settlement School be turned over to Sevier County as fast as the county could assume the burden.

By 1943, the community and the Fraternity convinced the county that it should shoulder the responsibilities for basic education. Gatlinburg, they argued, should receive as much as the county gave the other schools within its boundaries. A satisfactory lease-agreement was drawn up between the Fraternity and the county to cover 25 years. The Fraternity allowed the use of its high school building and playground for a rental fee of $1 per year. In exchange, Pi Phi retained the privilege of supervising the curriculum and having equal voice with the county in selecting teachers, 50 percent of who might be members of the Fraternity. A secondary agreement with the Sevier County School Board gave it the use of the grade school building until conditions made it possible to build a new elementary school on land adjoining the Pi Phi property, which was to be purchased by the county.

The insurance and maintenance costs were to be met by the county. The arrangement proved to be less than satisfactory. It was soon discovered that the basic responsibilities assumed by Sevier County were not all that was desired or needed at the school; consequently, Pi Beta Phi supplemented the program. The county supplied the faculty to teach basic subjects, but they were not able to teach all the courses which would make the school accredited. So, with the loan of the Pi Beta Phi School equipment and the addition of teachers secured and paid by the Fraternity, the school became fully accredited. Pi Phi supplied music, physical education and craft teachers as well as the necessary materials.

In 1947, the county again turned to Pi Beta Phi after two years of seeking a site for the new buildings and an athletic field. The only land was appraised at a prohibitive cost. In order for the new buildings to meet Tennessee's requirements, the Fraternity deeded 1.8 acres and leased sufficient land for playground purposes on a 50-year lease. The first modern grade school, the Pi Beta Phi Elementary School, was built on the site by the county in 1950. A few years later a gymnasium and a cafeteria were added. By 1962, plans were underway for a consolidated county high school. In 1968, the Settlement School elementary and secondary educational programs were discontinued when they became part of the Sevier County school system. The high school moved out Route 321, four miles on Proffitt Road to a new building. It consolidated with Pittman Center High School to become the Gatlinburg-Pittman High School.

After the county assumed responsibility for education, the settlement school and its summer craft workshops evolved into Arrowmont® School of Arts and Crafts.

To read more about Arrowmont, please click here.

By May Lansfield Keller, Maryland Alpha and Grand President Emeritus, written in 1931 at the request of Dr. Edith Gordon, Ontario Alpha and Settlement School Chairman.

“In August 1910, Miss Emma Harper Turner, Mrs. Anna Pettit Broomell and I, acting under authority granted to us by the convention in Swarthmore, went to Knoxville to choose a site somewhere in the mountains of Tennessee in order to found a Pi Beta Phi Settlement School for the mountain people of the Appalachian region.

We investigated sites, we visited association meetings, and we talked to various people interested in schools, but on the third day we had not yet found a place, and both Miss Turner and Mrs. Broomell had to leave that night. About 6:30 a telephone call came from a Mr. Drinnen at Gatlinburg inviting us to come to Sevierville the next day, saying that he would drive us on to ‘the burg.’ After discussion I decided to remain and go on alone the next day, trusting to providence and a strong constitution.

Bright and early the next morning I was on my way, the train puffed and chugged along, and I had full opportunity to study mountain types firsthand and also the beautiful woods as we stopped about every 10 minutes. Arrived at Sevierville, a man of medium height stepped up to me and said, ‘Drinnen’s my name, I am glad you came, you know you have kind of that healthy look, and you have 17 miles of the worst road in Tennessee to go over.’ Unabashed by this, I inquired when we were leaving, and was informed that I would ‘have to stop the night in Sevierville and leave at 5:00 the next morning.’ This arrangement completed, I went to the only hotel and was informed that everything was full. Seeing my consternation, however, the daughter of the house volunteered to give me her room, which was turned over to me immediately with no preliminary fussing over clean linen or any such trifle. It was on the first floor, everything was wide open, but the bed was fairly comfortable, and I slept well. At 4 o’clock the establishment began to arise, two sheriffs brought in a huge still, which was deposited just outside my window, and I began to sense local color. I ate my breakfast with a dozen men, not a woman present except the waitress, and a few moments later Mr. Drinnen arrived with horse and light buggy.

The morning was perfect and all went well until we came to a stream so high that when we forded it, the water washed over the floor of the buggy. We rocked from side to side, the water splashed, but we came through safely, and I breathed a sigh of relief. The next important event was the decision as to whether it would be better to stick to the road or go up the bed of the creek. The creek bed was full of boulders, but was really so much better than the road that we were glad that we had chosen as we did, when we saw the plight of a cart or two stuck in the mud on the road.

We next stopped at a one-room schoolhouse where a youth was instructing, who had just finished the fifth grade himself. He was teaching a geography lesson and was so visibly embarrassed by our entrance that Mr. Drinnen made a speech to help him out and then said that I would also address the school. I told them of the Pacific Ocean, the fish of many colors, and the sub marine gardens at Catalina, all the time observing the eyes growing bigger and bigger, until one apple-cheeked, brown-eyed boy could stand it no longer and burst forth with the question, ‘Deed, Miss, ain’t you lying?’ For the first time he had heard the ocean described by someone who had seen it.

We continued our journey, past the precipice where the remains of a buggy lay that had gone over the edge a few weeks before, and at another critical point met a team. I hung on, Mr. Drinnen continued to drive slowly with the left hind wheel a quarter of an inch over the edge, but we made it, and one more thrill was added to the list.

We arrived at Gatlinburg in time for dinner. There was not a two-story house in the place, and the one-room schoolhouse was in such a state of dilapidation that the floor was full of holes. I was taken to Ephraim Ogle’s for dinner, and again I had the experience of dining alone with the men while the women served. I chased beans around my plate with a two-tined steel fork, until I learned how to spear them, ate corn dodger and ended with pie and coffee.

After, the men accompanied me to the church and there I talked of our plans for the school, etc. They were suspicious. … I assured them we did not intend to proselyte for religion. Then came the questions: ‘How old be ye?’, ‘Why be’nt you married?’, and many more of a personal nature, but not impertinent, as they were really interested. As they became convinced that I was not trying to put anything over on them, one after another rose to say how he had no education, but that he wanted it for his children, and if we would only bring them the school and the teachers, they would do all they could to support it. They even ventured at that time to consider giving the land, if we would promise to keep the school running. No woman was present at this meeting; they were shy and silent, but they were also curious and one or two expressed the hope later that I would come again.

As time was passing rapidly, and we had that 17 mile drive still before us, I said goodbye, promising to think it over, and report favorably on Gatlinburg if I could. As we drove along the road, looking back I saw the sun shining on the top of Mount LeConte and the tiny settlement of Gatlinburg in deep shadow nestled in what seemed a cup in the hills. From that moment I knew what my report was to be. Education had to be brought to these people of the hills.”

By Dr. William S. Taylor, Dean of the College of Education at the University of Kentucky

“Any honest appraisal of the work of Pi Beta Phi will show definitely that the Fraternity has been instrumental in raising the intellectual level of the community, in building character in its people and in establishing good habits of life among the citizens of a remote area in great need of educational service. When Pi Beta Phi became interested in Gatlinburg, no one dreamed that the Great Smokies would some day become one of America’s most beautiful national parks. Pi Phi did its work in this community in such a way as to gain the respect and good will of the families of the community whose children attended the school organized and operated by the Fraternity. The children were encouraged to go through high school, to attend college and make themselves useful citizens of the community and the state in which they live. So well has the Fraternity done its work that the people who were property owners in the community have continued to grow with the community, and today, 30 years after Pi Beta Phi went into the area, the original families of the community are still the property owners with the business of Gatlinburg in their hands. I do not know another community in the United Stated that has grown as rapidly as has Gatlinburg, nor one in which the original families have been able to profit as greatly from the new business and increased values of property. … Pi Phi can rightly claim a great portion of the credit for providing these people with the kind of education which enabled them to grow with their community.”

In 1924, a trademark was sought for articles made at the school, and Grand Council suggested a contest be held. Alice Wallace Wright, a Wyoming Alpha, had the winning design. This design was used as a basis for the trademark “Arrowcraft” when it was registered by the United States government. By 1926, the industrial work was taking up much of Miss Evelyn’s and the teachers’ time. In addition to their school duties they were buying, packing, shipping, storing and tending to the endless details of running a craft business. That spring, the Arrowcraft Gift Shop was established on an experimental basis by Texas Alpha Harmo Taylor and North Carolina Alpha Lois Rogers. The shop first opened in the Teachers’ Cottage and then moved to Stuart Cottage.

During the first month, sales totaled $1,000. The shop was only open during the summer and between September and December. There were many orders from alumnae clubs. Lois Rogers opened the Arrowcraft Shop in April 1927 on a year-round basis. In 1929, $22,000 was paid by the school to the makers of the craft products. In 1931, upon the completion of the new Mountain View Hotel, a Pi Beta Phi Shop was opened in the hotel. Pi Beta Phi had been the first to provide a market for the mountain crafts, but by 1931 there were nine other shops in Gatlinburg selling weaving and other hand-crafted products. In 1940, a new Arrowcraft Shop was constructed on the Parkway.

A 1939 brochure noted, “Perhaps Pi Beta Phi’s outstanding contribution to Gatlinburg has been its part in the revival of weaving. The school furnishes not only the instruction, but also a market for high-grade weaving and basketry, wood and metal work, and its workers’ products have gained nationwide reputation for artistry and craftsmanship. The woven products shown in our shops are done in the homes of the weavers on their own looms, though supervised and designed by our weaving teacher.”

The Arrowcraft Shop has exhibited in most of the premier art exhibitions throughout the country. In 1931, the Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (now known as the Southern Highland Craft Guild) was formed, and the Arrowcraft Shop was a charter member. The guild operated a cooperative retail shop, the Allenstand Cottage Industries, in Asheville, North Carolina. In 1935, the Arrowcraft Shop bought shares of stock of the Southern Highlanders, Inc., a craft guild that had a shop at Norris Dam, 60 miles from Gatlinburg. Through its membership in the Guild and the Southern Highlanders, Inc., Arrowcraft shared in a nationwide cooperative effort toward a renaissance of American arts and crafts.

The first Craftsman’s Fair sponsored by the guild was held on the Pi Beta Phi grounds in 1948. The fair presented the opportunity for people to see demonstrations and well-planned exhibits of many diversified crafts from the area.

Arrowcraft had established one of the few examples of cottage industries in the Unites States. Many distinguished foreign guests who wished to promote home industries in their countries had been sent by their governments to study the project. In the early days of the weaving department, many of the weavers were mothers of young children. Weaving for the shop allowed them to stay home, yet still earn money. During one five-year period, 104 babies were born to shop weavers. Pi Phi rules required pregnant weavers take two months off prior to delivery and two months off following the birth.

The years of major weaving production were from 1935 to 1945. There were never less than 90 weavers, and they each earned between $150 and $300 a year for part-time work. In 1940, the U.S. government required proof the Shop was complying with the minimum wage, which was then 40 cents an hour. An Arrowcraft study confirmed weavers received between 45 cents and 50 cents an hour, depending on their weaving speed.

From 1969–1970, 62 weavers produced 20,000 tote bags and 15,000 daisy chain placemats, and 70 other craftsmen were kept busy.

While it had operated successfully in its early years bringing more than $1 million to its craftsmen, in later years the Arrowcraft Shop was unable to remain a viable enterprise. In 1994, Arrowcraft, Inc. was dissolved by the Arrowcraft Shop Board of Directors. The building was leased to the Southern Highland Craft Guild, which ran a similar store under the name of “Arrowcraft, a Shop of the Southern Highlands Craft Guild.” The shop closed in 2015.

Pi Beta Phi had played a major part in the crafts revival starting from the first basket-making workshop in 1914. Arrowcraft had given the people a way to earn money using skills many already knew. Pi Phis provided a marketplace and handcrafted items were shipped across the country. People who had never been to Gatlinburg knew of the wonderful products made by the area’s craftsmen. Pi Phi took this long association with the crafts movement and made it the focus of its philanthropic efforts.